There are a few types of cars that provoke an emotional response quite like the American muscle car. They are the automotive icons of a tumultuous era—one of the most violently American and at the same time, a dark period for those who lived through war and civil strife of the 60s. Our parents raised us to appreciate them, as some type of lost piece of their young adulthood. We’ve heard the memories about how they ‘had the only one in town’ or that it was the car they picked up mom for the ‘first date’. These are of course cliché stories we have all heard, but nonetheless, they are often true.

I grew up without any mythical muscle car stories. I didn’t hear about those blacktop heroes racing through the night. Or the epic all-nighters getting the car ready for the weekend drags. I yearned after my friends who were told tall tales by their fathers; of the ‘68 Firebird 400—one they’d never find again—or the ’67 Satellite 440ci that could break traction into fourth gear and was nearly totaled one late night racing.

These stories were an inspiration for me. I listened when they were told, but settled for learning about cars through video games and popular media. The stories I heard would never be mine. I could never pass down these stories—they belonged to someone else. They were stories that would belong to my friends one day; they were to be the stewards. I’d have to go make my own.

Stumbling upon a muscle car

My teenage years were spent foraging for a Japanese import, not a muscle car. I wanted to be a trendy ‘tuner’ with the lowered DC2 Integra and fit in with those ‘popular’ kids. I stumbled upon a 1971 Camaro 350 that was crashed, yet salvageable, for my first project. For a mere $300 it looked exactly that you’d think it would for the price—terrible. It would soon be known as my ‘La Bamba’ car, as my uncle would coin it.

The 1971 Camaro was previously Mulsanne Blue. This color was scraped off—“with a razor blade” per the prior owner—and it was rattle canned flat white. I remember the car passing our school bus over double yellows. It was loud; the noise however didn’t seem to adjust appropriately with the speed. So basically, it was ugly, louder than it was fast, and also, crashed. The front end, in front of the radiator, was missing. There was a distinct dent on the passenger front fender that resembled the notch a can opener makes before it cuts the lid off a can of chili. As a kid, I wondered which pickup truck had a front end like a can opener to do this amount of damage.

“I didn’t bleed the brakes right and it lurched forward at a stop sign,” was the excuse for the crash I heard as the seller used a ball-peen hammer to mount the positive battery cable onto the battery I’d just purchased. The car came alive. The pine needles were pushed off the windshield. “Just be careful when you come to a stop sign on the way home.” Somehow, this three-hundred-dollar battle wagon—driven by a 17-year-old without supervision or common sense to even check the brake fluid—made it a few short miles home without incident.

Fate, ultimately, brought me to sell my first Camaro as a necessary evil to advance myself in my career—an unintended consequence of climbing the social ladder. I ended up turning the $300 ‘La Bamba’ 1971 Camaro 350 into an $1800 car with around the difference in parts—no profit, no fruits of my labor other than not losing money. It somehow always ran, somehow made an 80-mile journey to college, and somehow never maimed or injured me. (Did I mention how the seats were never bolted down?) And from there, I moved away from muscle cars, I never thought life would bring me to another Camaro.

Enter in: Camaro number two

A half-decade and numerous cars later (almost 30 at the time of this writing), I had just sold my lifted XJ Cherokee when I began looking for the next project. I love the hunt: the exhausting search, the excitement of closing a deal, and the potential possibilities for the car—how crazy would my budget allow me to go? OEM plus? Or maybe a bit wilder?

I had a long list of potential vehicles. The goal was to find something that would appreciate or at minimum hold its value. (As the goal should always be, I hate losing money on projects.) The list was diverse, something from all around the globe: Mercedes 190E Cosworth, Mazda RX-7 FD, Nissan 300zx TT (my two prior Z32s had been NA), Integra Type-R, Mustang SVT, and even a Toyota Supra MKIV. The possibilities ran wild in my mind.

I began speaking to my good friend and mentor about my list. He recommended a Mercedes 500E. He mentioned something about MBZ and Porsche however, my mind stopped listening when I saw the prices for these cars. The more I searched the more I found that anything that will appreciate will already cost some serious money. (Funny how that works? Wished I’d bought a Ford GT when they were $120,000.)

We continued to toss around ideas for me until towards the conclusion of one of our phone calls he said, “Maybe you should buy my Camaro.” I had been down this road before—looking for an import and buying a muscle car. His Camaro was no cheap ‘project.’ This was an expensive car that needed several details sorted before it was done.

Realistically, it was an 80% complete car. The final twenty percent included, notably, the interior was untouched and terrible, and the front suspension needed an overhaul. I had some history with this particular Camaro: I assisted with dropping the gas tank and installing a new one when he first bought it. He’d considered buying my first Camaro but passed on it because he was not willing to buy a death trap. (He actually politely told me, “It needs too much work.”) Having already told him the car’s nickname was ‘La Bamba’ didn’t help change his decision either.

This one is much nicer—the seats were bolted down!

His Camaro was a 1970. It was a literal ‘Grandma car’ and left in a field, somewhere in Northern California, because ‘grandma didn’t need it anymore.’ It was unregistered since 1992. An original California car too—still wearing its original blue and yellow plates. Originally painted gold, with a tan interior, and equipped with a 307ci V8, TH350 transmission, and 10-bolt rear. It surely checked all the boxes Grandma wanted—none that I did. This car was bought out of the field for approximately $1,500 with the intention of building one mean streetcar. This had been my intention with mine, but my follow-through (and funds) were much less impressive than my friend’s.

Sadly, no pictures exist of the gold version of the 1970 Camaro. (It’s for the best, trust me, this car had fought a can opener too on its passenger rear quarter panel.) I was assured the paint job he had commissioned was near flawless. The paint took several years, as it was painted in between projects by a friend. The gold granny was turned hugger orange with black rally stripes for a mere seventeen thousand dollars.

The price was ‘take it or leave it’ and nearly double what I wanted to spend. I thought a chance to buy a car like this might never come up again—at least from someone I trusted and could call for advice. At a minimum, I needed to check it out. After several hours of driving, I saw before me the nearly completed Camaro I always wanted. I had seen an idea in my head of a Camaro similar to this as a teenager. The parts used to create this street machine were impressive.

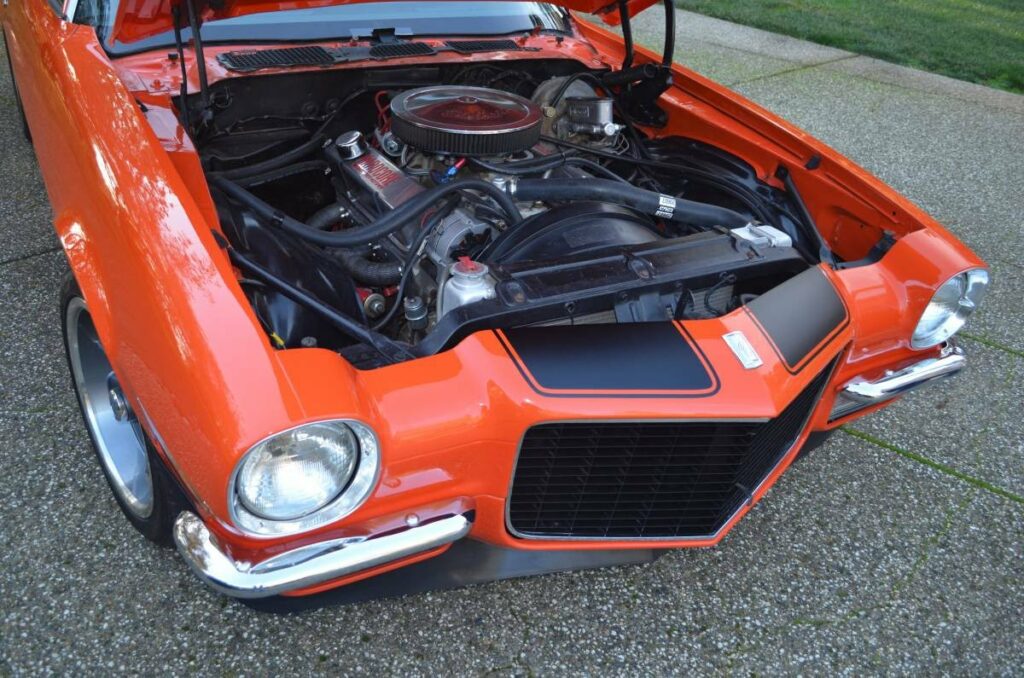

I pointed to the engine and learned “Chevy didn’t make that.” The engine was, instead, made by Bill Mitchell Hardcore and was their ‘aluminum lite’ small block—aluminum being the keyword because it was entirely aluminum and sub-500lbs. Rebello Racing in Antioch, CA had been hired to make the engine more reliable because the 427ci size made it a bit more likely to toss rods. The rods were shortened and pistons changed to bring the cubes down to 412ci, but the power remained close to the same: 550 horsepower.

Gone was the turbo 350 transmission. It now had three pedals instead of two. (Four if you include the emergency brake?) A Super T-10 transmission underneath was explained to me as being previously used in NASCAR, which sounded fancier than it was. In the rear, it had the best (arguably) rear end possible: the venerable Ford 9 inch with an LSD, Currie axles, full truss, 4.10 gears, all nicely powder coated silver.

I agreed to buy it and we slapped on the wheels and tried to start it up. It ended up having a flat battery, and the no choke 870 cfm Holley was being a fickle B*%C#, which should have been a major foreshadowing for me. The plan wasn’t to drive it home, so I’d have to figure out why it wouldn’t start later. This pretty Camaro came home on a flatbed, unlike the ugly battlewagon I’d driven home years ago. And like its ugly twin, it began its new life living in my backyard.

I was able to find time to do some bolt-on-type jobs, but I decided it would be best to take this car to a professional shop to finish it. (My ego now tells me I must explain I was deeply entrenched in a career, marriage, two toddlers, and hands that didn’t cooperate with the dexterity they used to.) I contacted a local hot rod builder to tackle the fit and finish and get this mean car tuned to drive reliably. It was a difficult decision to have someone else finish my car. The shop I knew was reputable, and I knew they’d do an excellent job but was I selling out?

After several months and many thousands of dollars, it was done. The interior was complete, the front suspension was aligned, and the engine was far more reliable. The car required a smaller carburetor with a choke to run without stalling or being impossible to cold start. I’d gotten it running with the smaller carburetor however, a friend had determined it ran like doo-doo because I’d stabbed the distributor in incorrectly.

Pretty car but bat-SH*% crazy

Ownership of this car was not without its fair share of hiccups. A wooden ladder fell into the passenger door, which cost fifteen hundred dollars to fix due to the excellent paintwork. And a drive belt EXPLODED into the underside of the hood, which cost a couple of thousand to fix but also allowed me to fit a cowl hood to fix a clearance issue. The power steering decided it didn’t like the twenty-first century or seeing a new ceiling (hood). The new power steering unit from Detroit Speed allowed me to remove some unneeded blood from my left hand during installation—a decent scar to this day. My ego was more cut when, like an idiot, I didn’t completely evacuate the old fluid and learned what ‘cavitating fluid’ meant when the reservoir cap blew off.

The drivability of the car suffered from the fact the engine was more for racing than cruising. All it wanted to do was go as fast as it could to redline at 6500 RPM. It did not want to pull away from stop signs at slow speeds, idle at less than one-thousand, and any three-point turn became a six for fear of the torque and clutch causing more body damage.

I spent more money on this car than any other car I’ve owned—except for those I’ve bought new. It was stressful to drive. I feared further physical and mechanical damage. All the money spend at body shops in such a short time was frustrating, to say the least. The thought of stalling it and not being able to restart it became anxiety-inducing after all the time spent tuning and paying others to tune the engine. The negative associations with the car became larger than the positives.

I tried to fix the things that I thought would make me happy to own it again. An EFI kit was several thousand dollars, but I was explained there was only a 50/50 chance it would alleviate the idle and restart concerns. An LS motor swap would be better, however far more costly. I was already very upside down in this build. I couldn’t swallow spending more money.

I decided the best thing to do was to sell. It was sold for a large loss – the biggest to date. I don’t regret owning the Camaro. It was a car that looked like a sexual tyrannosaur and ran like a raped ape when it decided to cooperate. People honked, waved, flashed headlights, and constantly asked questions about it. Even a homeless guy tried to get me to rev up the engine at a stop sign. I mean how could I not fulfill his request, being that he was holding a cardboard sign that said, “Not for alcohol.” I should hold up a sign next time I try to convince my wife to let me buy a project car. She’d see right through me too: “Not for a muscle car.”

Leave a reply